Thinking, Fast and Slow is a popular book I recently finished reading. Written by Nobel prize holder Daniel Kahneman, it summarizes decades of his work on researching cognitive biases, prospect theory, and happiness. It includes a lot of interesting insights from academia and the IDF (Israel Defense Forces). While there is a lot to take away from the 499 pages, I still find myself sharing relevant chapters with friends and family as they provide great insight in common phenomena. I wanted to highlight some of the most interesting and eye-opening insights in this post in a short format. Overall, this book has helped me think more rationally as I became more aware of my own biases.

Kahneman argues for a dichotomy of thought between System 1, the fast thinking, and System 2, the slow thinking.

System 2 is easily stopped by distraction because it requires attention. Insight: A state of flow can only be achieved with minimal distraction.

The Halo Effect: If someone is wearing a halo, they can sell you any bullshit. Insight: Presentation is important, so present well, leave a good impression because it can add weight to your pitch.

Pupils dilate when using system 2. Involuntarily.

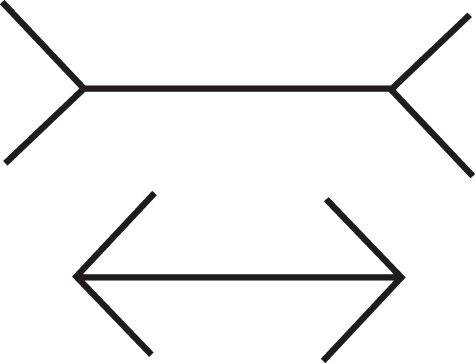

There are many different types of illusion and biases, and one of the easiest introductions to illusions is a visual one: the Müller-Lyer illusion (the lines are the same length):

Being cognitively busy makes you more selfish, judgy, and more. It also results in ego depletion. Insight: Keep balance and awareness of your mental state when you have a lot of work on your mind.

WYSIATI: What you see is all there is. We often want to see things in something, but often there is nothing deeper. Insight: When analyzing data, we see what we want to see but sometimes is there just no pattern. WYSIATI.

Even student at Ivy Leagues can fail simple riddles like:

- A bat and a ball cost $1.10. The bat costs one dollar more than the ball. How much does the ball cost?

- People say $0.10 (duh). But if the the bat costs a dollar more then the total is $1.10. The ball costs $0.05.

We often make totally irrational guesses, for example a significant amount of participants in a survey guessed that the number of murders in Detroit is higher than the number in Michigan (within the same survey! If this surprises you that this is wrong, recall that Detroit is a city in Michigan)

Delaying gratification is a sign of intelligence

Associative activation: “Bananas Vomit” triggers system 1, uncontrollably, and likely brought unpleasant mental images or even physical reactions like raised hairs.

Priming effect: You are temporarily more likely to complete the word fragment SO_P as SOUP than as SOAP if you have recently seen or heard the word EAT. It goes even further, as people primed with elderly theme words like Florida, bald, grey, or wrinkle unconsciously walked down the hall as part of the experiment slower than those who were not primed with an elderly theme.

The most persuasive messages are legible and memorable, not fancy. Insight: Keep your pitches short, simple, to the point.

Font matters a lot in how effective messages are. Insight: Rice out your terminal and editor using monospaced fonts with ligatures, use something that’s pleasing to look at.

Mere-exposure effect. Simply repeating something makes it better, more believable etc. Insight: repeat yourself more often.

An interesting theory on the origin of religion:

The psychologist Paul Bloom, writing in The Atlantic in 2005, presented the provocative claim that our inborn readiness to separate physical and intentional causality explains the near universality of religious beliefs. He observes that “we perceive the world of objects as essentially separate from the world of minds, making it possible for us to envision soulless bodies and bodiless souls.” The two modes of causation that we are set to perceive make it natural for us to accept the two central beliefs of many religions: an immaterial divinity is the ultimate cause of the physical world, and immortal souls temporarily control our bodies while we live and leave them behind as we die.

- Context is incredibly important. Asking people how happy they are after triggering an emotional responser such as “How many dates have you had last month?”, which can trigger happiness or sadness, sets the frame for the next question of “How happy are you?”

- The law of small numbers. We place exaggerated faith in small samples. Insight: We believe and act in irrational ways, for example hating flying because we saw a plane crash on the news month ago, when it is actually by far much safer than driving, yet few fear driving. We are scared by a couple of illegal immigrants committing crimes, forgetting the vast majority of harmless, hard working people. We see an 18 year old die of Covid-19 on the news and fear for our life, yet forget that the vast majority of deaths are found among the elderly and immunocompromised.

- The anchoring effect. We depend heavily on an initial piece of information given when making decisions, even if it completely irrelevant and independent. For example

- Insight: Remember this when negotiating.

Various studies have shown that anchoring is very difficult to avoid. For example, in one study students were given anchors that were obviously wrong. They were asked whether Mahatma Gandhi died before or after age 9, or before or after age 140. Clearly neither of these anchors can be correct, but when the two groups were asked to suggest when they thought he had died, they guessed significantly differently (average age of 50 vs. average age of 67).

Availability heuristic: Judging frequency by the ease with which instances to mind. For example, we exaggerate the likelihood of divorces in Hollywood because these events are much more publicized. Another example I mentioned earlier is plane crashes. Insight: I see this couples tightly with the law of small numbers, but I take this heuristic as being more within a media context.

Awareness of one’s own biases is good, it can contribute to peace in marriages.

An availability cascade is when media reports of minor events are hyped, lead to a panic, and demand of large-scale government action is produced, which takes away resources from actually more important things. Insight: There are many irrelevant things that are hyped by the media, leading minority groups to demand extreme action from governments. This also works with fake news, so for example, fake news spread about 5G being harmful leads a small number of people to react very strongly and demand government action, e.g. launching petitions signed by tens of thousands.

Probability neglect: Again, tying in closely with the law of small numbers, we think irrationally of probabilities as we only consider the numerator, and the denominator. Five deaths per day from Covid-19 is nothing when there are almost eight thousand deaths per day in the US from other causes.

Base rates. Humans are terrible at them. We tend to assign things to unlikely classes, forgetting the overall likelihood of being assigned a class. Insight: Apply Bayesian reasoning: anchor your judgement of the probability of an outcome on a plausible base rate, and question of the diagnosticity of your evidence

- Less is more: for example, consider Linda, a “single, outspoken, bright, philosophy major” and pick one:

- Linda is a bank teller

- Linda is an insurance sales person

- Linda is a bank teller and active in the feminist movement

- People incorrect choose the third option despite Linda is a bank teller ∩ Linda is a feminist will mathematically always be less likely than Linda is a bank teller

- Less is more: for example, consider Linda, a “single, outspoken, bright, philosophy major” and pick one:

Regression to the mean: Kahneman recounts a story from his career in the IDF, where he recommended positive reinforcement to flight instructors rather than punishment. An instructor disputed his recommendation, recalling that cadets performed better on the next maneuver after being screamed at through their earphone, but the supposed effects of instructor feedback on the following performance are actually

…due to random fluctuations in the quality of performance. Naturally, he praised only a cadet whose performance was far better than average. But the cadet was probably just lucky on that particular attempt and therefore likely to deteriorate regardless of whether or not he was praised. Similarly, the instructor would shout into a cadet’s earphones only when the cadet’s performance was unusually bad and therefore likely to improve regardless of what the instructor did. The instructor had attached a causal interpretation to the inevitable fluctuations of a random process.

On overconfidence: We arrogantly believe we can tell the future, we believe others when they say they can. For example, CEO compensation does not correlate with performance, and stock pickers rarely beat indexes, yet we trust them as “experts”

Outcome bias: Hindsight is always 20/20, even more so for decision makers who advise others such as physicians, financial advisers, CEOs, or politicians. We are prone to blame decision makers for good decisions that worked out badly, and don’t give them credit for successful moves that appear obvious only after the fact. When the outcomes are bad, the clients blame them for not seeing the writing on the wall, but forgetting that it was written in invisible ink that became legible only afterward. Insight: Actions that seemed prudent in foresight can look irresponsibly negligent in hindsight.

Illusion of validity

Simple combinations of scores does better than human intuition, for example NICU checklists. Six dimensions is a good number.

Intuition is recognition

Planning fallacy: Overly optimistic forecasts of the outcome of projects are found everywhere.

Sunk cost fallacy: We continue investing resources in failing/failed endeavors just because we already have. Common reason why projects balloon in price or length. Insight: Cut things loose

Competition neglect: 90% of drivers believe they are better than average

We focus on our goal, anchor on our plan, and neglect relevant base rates, exposing ourselves to the planning fallacy. We focus on what we want to do and can do, neglecting the plan and skills of others. Both in explaining the past and in predicting the future, we focus on the causal role of skill and neglect the role of luck. We are therefore prone to an illusion of control.

Prospect theory: For example, for some individuals, the pain from losing $1,000 could only be compensated by the pleasure of earning $2,000.

Wealth and happiness is felt in relative terms. Insight: We are happy when we get that promotion from 100k to 120k, but we are not happy at 100k. For many, 100k would be a dream in the first place.

Theory-induced blindness: When you accepted a theory and used it, you start to accept it as truth and see everything through its lens

Endowment effect: We value things more just because we own them

We are willing to pay for certainty

Frequency format matters - 1 in 1,000 has more impact than 0.01%

We have stronger emotional reactions to actions that yielded a negative outcome than to outcomes caused by inaction

Duration neglect & the remembering self: We remember negative experiences better

Focusing illusion: “Nothing in life is as important as you think it is when you are thinking about it.”

Affective forecasting: Permanent life circumstances have little effect on well-being. We imagine that we will be happy in the southern California sun, but in reality people are happier in Scandinavia. A similar effect is seen in people who become disabled. After they pass a period of grieving, their happiness returns to normal. Insight: The grass is always greener.

These are just some short summaries of some of the main topics covered. I do recommend reading the whole book.